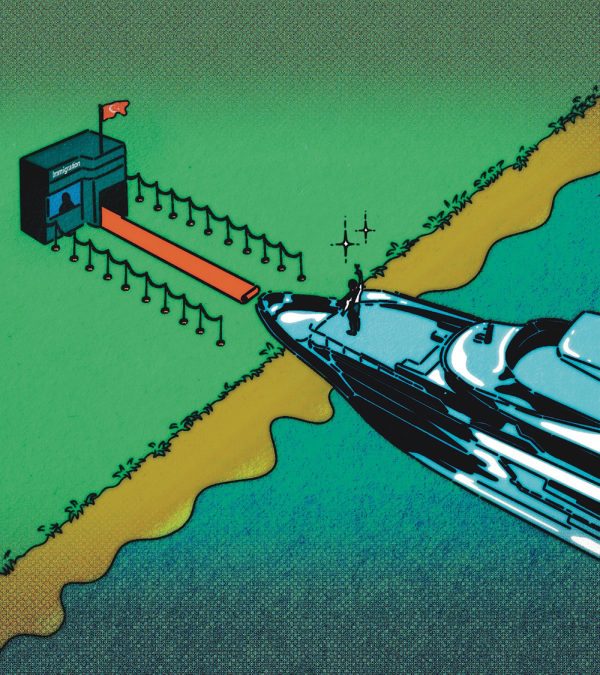

A growing number of states are willing to sell citizenship and the privileges it brings — if you can afford to pay. The lucrative trade in “golden passports” exposes the dark side of capitalist globalization and its unequal valuation of human life.

In October 2017, the tiny country of Montenegro was abuzz. Nestled in the mountains along the Adriatic coast and with a population of merely 620,000, it’s a place that has been overlooked by many. Formerly a part of Yugoslavia, it remained an appendage of Serbia until it gained full independence in 2006.

Given the country’s size, it didn’t take much to create a lot of hype for the Global Citizen Forum. In the capital city of Podgorica, billboards projected mammoth images of the event’s headline speakers, a glitterati lineup including actor Robert De Niro, musician Wyclef Jean, and General Wesley Clark.

Along the coastline, black-and-gold forum banners lined the highway, challenging drivers to “inspire change” and “provoke innovation.” At the airport, posters greeted new arrivals by proclaiming, “The future starts now: keep the conversation going.” Over two days, nearly four hundred participants would gather in the small Balkan country to discuss the most pressing issues facing the world today. Millionaires milled around the samovars and chatted with DJs and supermodels. Prime ministers and politicians dropped in by helicopter. Filling the spaces in between was a hodgepodge of philanthropists, NGO workers, bankers, creatives, and a few royals.

There was little hint as to what was actually financing the lavish proceedings: golden passports.

Citizenship by Investment

Several guests I talked to had never even heard of golden passports. When the topic came up, it was almost in passing. Still, it lurked in the background. A representative from the Montenegrin government in one session described the new citizenship by investment (CBI) program they were planning:

It’s a way to attract people who have knowledge and experience to come and teach others, and to move the country forward. If executed and monitored properly, it’s a big opportunity for countries like Montenegro. . . . We don’t want to sell passports; we want to buy excellence.

I spoke with him and a few officials from other countries that were looking to develop their own CBI programs — Georgia, Macedonia, and Moldova were all showing interest.

A civil servant from Armenia explained to me over coffee that his country, lacking oil or gas, was exploring ways to build a business environment that would attract foreign capital, and it saw CBI as a means to develop its competitiveness. “We’re looking for a tool to place the country within the right networks,” he clarified. If inserting oneself into elite networks was the goal, the Global Citizen Forum was the place to do it.

As of 2025, at least nineteen countries had a legal basis for naturalizing individuals who invest in the country or donate a specified amount, with over a dozen hosting active CBI programs. The Caribbean is home to five: Antigua, Dominica, Grenada, Saint Kitts, and Saint Lucia. The greater Mediterranean region is another hotbed, with Turkey, Egypt, North Macedonia, and Jordan offering programs, even as Malta, Cyprus, and Montenegro exit the scene. In Asia, Cambodia has a CBI program, and in the South Pacific, Vanuatu has a smorgasbord of available options.

Until recently, CBI schemes have been the preserve of small island countries with populations of less than one million. For such microstates, a sizable injection of foreign funds brought through CBI can have a considerable economic impact. However, the landscape has recently begun to change as more substantial nations, like Turkey and Egypt, enter the game.

As other countries like Armenia, Croatia, Georgia, and Panama discuss options, CBI doesn’t seem to be going away anytime soon.

A Product in Demand

On the face of it, these programs appear minuscule. Only around fifty thousand individuals naturalize though them each year — a negligible number among a global population of eight billion people. Yet the significance of the figure is much clearer when placed in context. The population of likely consumers is relatively small — largely members of the nouveau riche from countries outside the Global North. Figures available from Malta, Antigua, Cyprus, Saint Lucia, and Dominica suggest that buyers mainly come from three regions: China and Southeast Asia, Russia and the post-Soviet countries, and the Middle East.

Some people from wealthy democracies may apply, including a growing number of US citizens. Driving demand, however, is a smaller population of wealthy peo-ple from countries with “bad” passports and authoritarian regimes. It’s the non-Western winners of globalization — those doing well on Branko Milanović’s famous “elephant curve” — who want it. For governments aiming high, these global elites are the target audience of citizenship for sale.

Yet not all countries have been equally successful in attracting investor citizens, despite the continuous growth of demand. In the early 2010s, investors went for Caribbean programs, which accounted for about 90 percent of naturalizations globally. By the middle of the decade, however, they began turning to new offerings in the Pacific and Mediterranean, and since 2018 have sent Turkey to the top of the charts. It’s now the country of choice for most investor citizens and accounts for around half of all such naturalizations globally. Even at the height of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, Ankara was approving around a thousand applications per month.

Citizenship as Commodity

Citizenship is not only an unusual commodity; it is also unusual as a commodity, which presents distinct challenges when building a market around it. States can shield populaces from the worst effects of the market by compensating them when markets fail. Yet in the case of citizenship, the state is both the key market regulator and the sole producer of the good, for in the contemporary world, only states make citizens. If a government does not recognize a grant of citizenship as its own, the status is null and void.

Even Stefano Černetić, Prince of Montenegro and Macedonia, had to face this reality. His high-society life, which included knighting Hollywood actress Pamela Anderson, came to an abrupt end when police discovered that this Italian citizen, with a closet full of fake uniforms and royal robes, was merely posing as the head of state. He could not even turn to his self-proclaimed kingdom for help.

Stateless people, like the Rohingya of Myanmar or ethnic Russians of Latvia, know the dire consequences that can result when a government disavows them as outsiders. Even if they once had claims to belonging, their citizenship no longer counts if the state doesn’t stand behind it.

The result is that the state is the only legitimate seller of citizenship. Even if bureaucratic hurdles extend the naturalization process, and even if chains of intermediaries connect the buyer and seller, the state must sign off on every citizenship transaction. As such, there can be no legal secondary market.

Sovereign Prerogatives

Because citizenship is a state monopoly, even its smallest incumbents — microstates of less than a million inhabitants, lacking the economic and military heft that we typically associate with statehood — can employ this tool to raise revenue. What matters is not size but sovereignty.

Effectively, the state wears two hats when it sells citizenship, serving as both the sole producer of the product and the ultimate rule-maker of the market. The double role has at times yielded ethically questionable but entirely legal cases of countries selling citizenship to the criminally suspect. Tadamasa Goto, a Japanese mob boss who became Cambodian for a sizable donation, is one example.

Still, when the state both structures the field of play and serves as an indispensable player in the game, it calls into question conventional assumptions about what is needed for a market to work. In the case of sovereign debt, for example, the possibility of default without compensation remains a looming risk because sovereign immunity limits the available tools for enforcing payments or seizing assets. Governments can also influence macroeconomic indicators, making it difficult for creditors to verify their economic health. To protect against such threats and secure liquidity, intermediaries with separate reputational risks enter the transaction.

Citizenship has its own version of sovereign debt default: nonrecognition. When, for example, Grenada closed down its economic citizenship channel in 2001 following pressure from the United States, it dealt with its investor citizens by simply refusing to recognize them as such, effectively erasing their citizenship. Similar incidents occurred in the Pacific across the 1990s.

However, this strategy becomes more difficult once these channels are formalized into full-fledged CBI programs. When citizenship is granted through an extended bureaucratic procedure involving a division of labor and external oversight, such willful disregard can more readily be challenged, and membership can be severed only through formal, legal denaturalization.

Deglobalization and Citizenship

If anything, the post-2020 process of deglobalization is likely to push demand for CBI programs even higher as people look for ways to guarantee access and opportunity should countries delink or seal themselves off into regional blocks. As states turn inward, supply also may increase among countries struggling with the economic fallout.

Even if globalization presses on, a different outcome is unlikely. CBI will continue to grow in a world of risk, uncertainty, and inequality — the hallmarks of the capitalist expansion that drives much of contemporary globalization. Demand for the programs will persist as long as countries continue to produce wealthy citizens looking to improve their mobility or opportunities, or for an insurance policy against their own governments. Supply is unlikely to falter as states with limited revenue sources turn to this source of easy money, particularly when other economic streams dry up.

Increasingly, our world is one of mobility rather than migration, in which people move — or seek movement options — with greater flexibility and on a shorter time horizon than is captured by the heavy notions of immigration and settlement.

But this does not render citizenship obsolete. Instead it becomes more powerful precisely because it is portable and still holds force even outside the granting state. A doctor who moves to a different country may lose her credentials, but the same does not hold for citizenship: you take it with you wherever you go.

For this reason, even in an age of mobility, citizenship still has fundamental importance, and its implications for global inequality are profound. Citizenship is about far more than a valued bond between sovereign and subject. It is the differences between citizenships that define their worth.

Rising Tides

Indicative of CBI’s future may be the most recent entrant into the coterie of golden passport countries: Nauru. Until 2023, the microstate gained about two-thirds of its revenue by hosting an offshore detention center for Australia. When individuals sought refuge in Australia, Canberra would have them shipped to a massive holding facility on Nauru. Over time, this became the remote island’s economic lifeline, employing as much as 15 percent of the local population directly and much of the rest of its twelve thousand inhabitants indirectly.

When the center was shut down in 2023, the government had to find a new hustle to make ends meet. This time it has tried the other end of the mobility spectrum: elite citizenship. In November 2024, it launched a new golden passport program enabling investors to naturalize for just $105,000 plus $25,000 in fees. But what does citizenship in Nauru bring? Not only a new set of documents but also visa-free entry to both Russia and the UK — an interesting combination, but one that hangs in the balance.

Nauru is facing even greater challenges with rising sea levels threatening the country’s very existence. As climate change presses on, it will be the poorer and more fragile island microstates that suffer the most, even if they have contributed the least to a crisis that does not stop at state borders.

Would a subaquatic country still be able to sell citizenship? The question may seem ludicrous, but it pinpoints the challenges that microstates face, leaving the people there to hustle as best they can. The delicacy of their position today underscores the complexities of global inequality and the geopolitical maneuvering that define our world.